Child trafficking in Benin: Difficult choices and devastating consequences

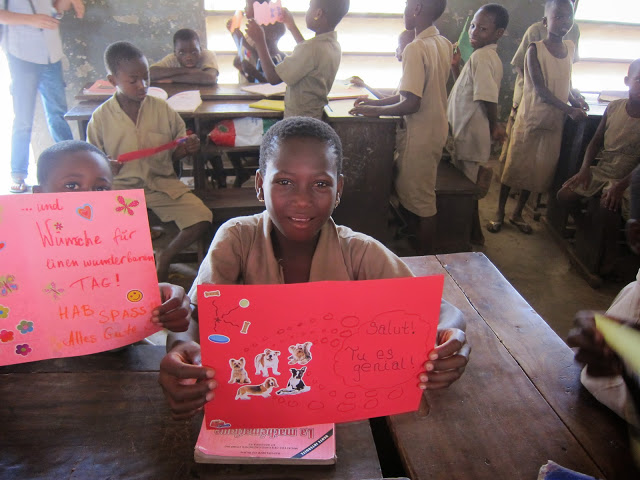

Azandégbé was just nine years old when he was sent to work as a laborer in central Benin’s farmlands. As he tells his story, he describes the tiring work under harsh conditions, and the abuse he endured before running away from the farm where he and his two brothers worked. Azandégbé walked 25 kilometers to the nearest town, where he slept in the market for two days before he was found and brought to Dagbé’s children’s home in the region.

The three brothers attended school for only a few years each and began working at an early age to support their family. Their parents never attended school and worked as farmers outside the town of Allada in southern Benin. When a local man promised the chance to travel and work in exchange for money, the boys jumped at the opportunity, but the resulting situation was far worse than they could have imagined. They were on their own, far from their family, and far from home.

According to one UNICEF study, an estimated 40,000 Beninese children are trafficked each year, most working in agriculture or household labor. Nearly all parents of trafficked children surveyed had little to no schooling, and all children reported working seven days per week with little attention paid to their health and wellbeing.1 The most common form of child trafficking in Benin is labor trafficking, including manual farming labor, and Vidomegon, a common practice where children are placed as domestic servants with richer families.

In Benin and throughout the developing world, child labor is a harsh reality that is accepted as an inescapable part of childhood. Although Beninese law sets the working age as no earlier than 14, many children from poor families leave school at an early age to help their family earn money. According to Mme. Hortense Offrin Chabi, regional director of Benin’s Ministry of the Family for the central Zou-Collines region, “Every child has rights. They have the right to attend school; they should not be victims of trafficking nor subject to economic exploitation. Children should not work before the age of 14… Unfortunately, there are people who engage in these practices, in some cases the children’s own family members. “

Nearly half of the population in Benin lives below the international poverty line of $1.25 per day, and women have on average five children.2 Educational expenses for families with multiple school age children, including fees, supplies, and uniforms can easily exceed a family’s monthly income. But above all, time spent in school and not contributing to the family’s income often represents an insurmountable opportunity cost. While most children leave school to assist with the family’s domestic or farm work, some enter into trafficking arrangements. Family members who place their children in trafficking situations usually have no understanding of the conditions under which their child will be forced to work.

What can communities at the heart of this problem do to combat trafficking? While many socio-economic factors contribute to the difficult choices these families make, awareness of the rights of children and the definition of trafficking is a key step. Dagbé has launched an anti-child trafficking awareness campaign with a network of village change agents in central Benin, partnering with local authorities and community radio to reach rural villages where trafficking is endemic. A pilot training seminar was held with 45 community leaders in 2012 and within 72 hours a shocking case of sex trafficking involving a young girl just nine years old was brought to the attention of local police.

What’s next for Azandégbé? He and his brothers want to start vocational training to be able to earn a good living, and they know that farming activities alone like those of his parents will not suffice. Although limited by minimal education, trade apprenticeships can provide boys like Azandégbé with job-ready skills needed start their own business. Azandégbé wants to become a mechanic, and his brothers want to become a taxi driver and a hairdresser respectively. While their childhoods were cut short by the harsh realities of labor trafficking, they still have their dreams. Dagbé’s staff is working with the boys and their family to place them in a vocational training program so that consenting to trafficking is never a choice they have to make again.

Sources

- Etude Nationale sur la Traite des Enfants. Rapport d’analyse. UNICEF. November 2007.

- UNICEF, Benin country statistics for 2012.