Service and volunteering have to be about the human person if they’re going to bear any fruit.

Sebastián Seromik

Hello Dagbé Friends,

A new year.

New beginnings are a great time to reflect on your roots. As a new member of Dagbé, I have more questions than answers, so I thought we’d start there. First order of business: the beginning. I sat down to interview our founder Sebastián Seromik and pick his brain about Dagbé. A transcript of our conversation follows.

Looking forward to a challenging and rewarding year ahead.

Cheers,

Cassie

Q&A with Dagbé Founder Sebastián Seromik

Cassie: As we’ve discussed before, I feel honored to be part of this board. So I want to start by saying thank you. And then I’ll kick off with a few questions about you. Where are you from? Where did you go to school? Where do you live now? What are you doing now? Ok, I guess that’s more than a few.

Sebastián: Haha, well thanks, Cassie. We’re also really grateful and excited to have you join the board. I was born and raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan. I studied business at the University of Michigan as an undergrad, have a master’s degree focused on social and professional ethics from Boston College, and am currently finishing an MBA at the Yale School of Management.

Cassie: And I know somewhere in between school you decided to join the Peace Corps. Tell me a little about that.

Sebastián: I joined the Peace Corps right out of college at 22 years old. When thinking about the next step after college, I felt that I needed to serve others in some capacity. I had been receiving all of my life and needed to take some time to give back. I looked around at different volunteer programs and was drawn to Peace Corps because of its international outlook. It also didn’t hurt that UofM has strong ties to the Peace Corps – President Kennedy announced that he wanted to form the Peace Corps when campaigning on campus!

Cassie: I’m definitely starting to connect the dots now. And where does Dagbé fit in this story?

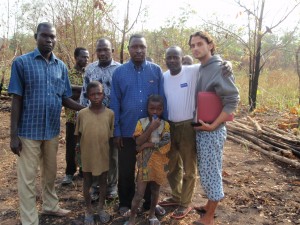

Sebastián: It was during my Peace Corps service. There was a clear lack of care for children who were in difficulty – orphans, victims of abuse, etc. One day, when saying hi to the local police (it’s common in Benin to walk into a building and say hi to people if you are walking past it) I realized that they had 7 Togolese children, from 8-15 years old in the jail. They were trafficking victims and there was nowhere else for them to stay. I had become close friends with a community organizer and one of the representatives from the Ministry of the Family in town. We all sat down one day to discuss what could be done and they wanted to build a center and start an organization that cared for children in crisis situations. That’s how we started the work.

Cassie: Was this your first experience with a non-profit organization?

Sebastián: My father has worked for non-profit organizations since before I was born, and as a result I have been around them all of my life. I have seen the way the mission of the organization drives the way it works and I have seen the sacrifices that organizations make in order to accomplish their missions.

Cassie: When did you first travel to Benin and what was your first impression? Did you have any fears or concerns about being placed in West Africa?

Sebastián: I arrived in Benin in July 2007 with the rest of my “class” of Peace Corps Volunteers. We arrived late at night, but I remember waking up the next morning and feeling a sense of peace. There were things that reminded me of some of the poorer areas of Mexico that I had seen but mostly Benin was an entirely new experience for me. I never actually had any fears about being placed in Africa. I was extremely excited from the moment that I heard the Peace Corps would be sending me there.

Cassie: I’m curious about your living situation. Tell me more about that.

Sebastián: I lived in Ouèssè for about two years. My house was in a neighborhood (quartier) called Adougou and was a three-room house with a long porch off of one side. The town had no electricity or running water, so once the sun set I had to rely on kerosene lanterns for lighting. I would finish dinner and take my guitar to the porch outside where I would play guitar in the dark for a little while before going to bed.

Cassie: What was most challenging about adjusting to life in West Africa?

Sebastián: The greatest challenge was to remember that I was the one visiting their country and that I could make those adjustments. It’s tempting to arrive somewhere and become frustrated about what is different and begin to think, “They should be doing things this way.” It’s in our nature to want others to adapt to our way of doing things. But if you try to do that in another country, you’ll quickly become very upset. Even though it’s challenging, it’s important to adjust that mindset from the outset so that other adjustments are easier to make.

Cassie: What was your assignment or goals while in Benin?

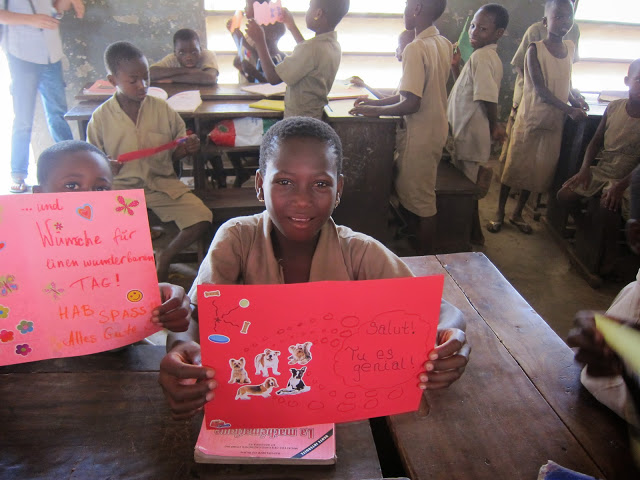

Sebastián: I was a Small Enterprise Development volunteer, which meant that I worked with local trade associations to train them in basic accounting and marketing practices. Beyond that, we were encouraged to get involved in other projects if we had the chance. I taught music theory classes, guitar classes, started a penpal initiative between a Beninese school and a US school, helped start a softball team with middle school students, worked on geography projects with primary school students, and provided consulting for small businesses in the region, among other activities.

Cassie: Wow, you definitely stayed busy! Were you able to fit in any travel during your time in West Africa?

Sebastián: I traveled throughout most of Benin during my time there, including one safari trip to the Pendjari National Park in the northwest. I also traveled overland to Ghana a couple of times for very short one or two day trips. Finally, my sister and brother-in-law adopted a little boy from Ethiopia during my service, and I had the chance to fly to Addis Ababa in Ethiopia to meet my new nephew. That was an incredible experience.

Cassie: I’ve seen a few photos from your adventures, and they’re incredible. I’m really excited to share. Ok, I want to switch gears a bit and try to understand what a day in the life was like. Tell me about a typical day.

Sebastián: I would wake up, pray, and have my morning coffee. My parents know me too well – their care packages consisted of ground coffee that I would prepare every morning using a French press that fit with my Nalgene water bottle. I would typically head out into town in the morning to talk with friends and townspeople and purchase anything that I needed from the market. On my way back I would often stop to visit Victor, my work partner on the children’s center project, and talk business. I would then work for a few hours at home, eat lunch, and then walk down to the work site to see the construction progress and have the workers explain the process to me. When I would return I would often find the neighborhood kids playing on my porch. I would work for a couple of hours inside while they played outside and then as the sun was setting I would make dinner. After dinner I would play guitar and read for a while and usually be in bed by 9 or 10pm. It’s amazing how much earlier you go to sleep without electricity!

Cassie: I suppose that’s one way to get more sleep. Maybe I should try that. Speaking of food, I’m so curious to hear about what you ate.

Sebastián: For breakfast, people in Benin often have a type of porridge called bouille which is made from cornmeal. For lunch and dinner, the meals were often very similar. The most common meal was called pâte (pronounced “pawt”); it was also based off of cornmeal and had the consistency of mashed potatoes. You grab a chunk with your hand and dip it into a sauce that is usually tomato-based with peppers and onions. Another common meal, and one of my favorites, was pounded yams called igname pilée. It’s yams mashed like mashed potatoes and dipped into a sauce – my favorite sauce was a peanut sauce. Usually a small chunk of protein accompanied the meal – most often fish, but sometimes chicken, sometimes bush meat, and sometimes a cheese called wagashi made and sold by the Peuhl ethnic group.

Cassie: What is your favorite memory of your time spent in Benin?

Sebastián: Wow, what a difficult question. If I could only choose one memory, there’s one in particular that sticks. While I was raising money to build the children’s center, I would travel every Monday morning to Parakou, a city two hours away that had internet access. I would work all day and through the night, and all of Tuesday – usually 24-28 hours with short breaks to eat and maybe sleep a couple of hours. Tuesday afternoon I would head back to Benin. On Monday mornings I would wait for the taxi at a makeshift gas station (the gas was sold in different sized glass containers of varying capacities). The family that ran the gas station was a young couple and their four daughters, between 2 and 10 years old. Each Monday morning I would wait with them, chatting with the mother and father and playing games with the daughters while they excitedly told me about school, their dog, and anything else. Every Tuesday afternoon those little girls would wait for me to get home and run to give me a hug when I got out of the taxi. It was an amazing feeling of belonging thousands of miles from my family, from my country, and from the community I’d known all of my life. It was those moments that made me realize that I did belong and I was loved even over there.

Cassie: I would be grateful to feel a sense of belonging in a place that is half a world away. That’s truly incredible. What was the most meaningful relationship you developed in the community? Was it the relationship with this family?

Sebastián: No, I would have to say it was my relationship with Victor, the director of our center in Benin. We not only worked together, but he opened his home completely to me. His family became my family; they invited me for meals, they supervised my home while I was traveling, and he even named his baby son after my father.

Cassie: In what ways are you most proud of how Dagbé has helped the community in Ouèssè?

Sebastián: Dagbé was established with a clear mission. We are not about numbers or having an expansive reach. We are dedicated to the human person – to changing lives. I am most proud that our staff and everyone who works there is recognized within the community not just as an aid worker but also as a family member or mentor to the children that we serve. Our staff realizes that they are not simply providing a roof for the children and somewhere to lay their heads, or food, or clothes. They’re also providing the comfort and compassion that a family and a home do. That is what I am most proud of and what I hope that people take away when they hear about our work.

Cassie: What is the greatest lesson you learned from your time in Benin?

Sebastián: I learned that making a difference is about being present to the person in front of you. I realized very quickly that I wasn’t going to change the world, eradicate poverty, or end child trafficking. What I could do, however, was walk alongside the people that I was with in that moment in life, listen to them, meet their needs when possible, but also just be with them. Service and volunteering have to be about the human person if they’re going to bear any fruit.

Cassie: I don’t know if I have ever heard someone summarize the value of service more perfectly. Thank you, Sebastian.

One of our most important tactics in fighting against child trafficking in Benin is educating the community. Cases of trafficking fly under the radar, and in a country where the sight of children laboring in fields is a relatively common one, many people are unaware just what a child’s rights are what should happen in cases where a child is mistreated.

One of our most important tactics in fighting against child trafficking in Benin is educating the community. Cases of trafficking fly under the radar, and in a country where the sight of children laboring in fields is a relatively common one, many people are unaware just what a child’s rights are what should happen in cases where a child is mistreated.